Effects of low-carbon cement on the concrete curing process

The cement industry is going to great lengths to lower the high carbon emissions generated during cement production. One important aim – among many others – is to reduce the proportion of clinker as the main emission source. This article explains the effects of using low-carbon cement on the curing process of concrete products.

Producing cement and concrete generates a major share of global carbon emissions, of which a substantial proportion is attributable to the production of Portland cement clinker as the main constituent of cement. Cement clinker is produced by firing a raw material mix of limestone (CaCO₃), clay, and sand and then grinding it in rotary kilns at about 1,450°C. In this process, about two thirds of the carbon emissions are generated through the chemical conversion of limestone to calcium oxide (CaO) and carbon dioxide. The remaining third can be attributed to the combustion of fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and gas, which are essential for reaching the required high firing temperatures.

Roadmap of the cement industry

The cement industry has drawn up a strategic roadmap to become climate-neutral by 2045. This strategy utilizes three main levers:

Firstly, replacing fossil fuels by substitute fuels or electrification. Today, over 70% of fossil fuels are already being replaced by biogenic fuels or fuels made from waste materials.

Secondly, developing low-carbon types of cement. This approach aims to reduce the proportion of clinker in the cement by increasingly using granulated blast furnace slag, fly ash, or calcined clays as ground additives. This modification is commonly used in the cement industry and lowers the proportion of high-carbon clinker and emissions per ton of cement by up to 40%.

Thirdly, CCS and CCU technologies (i.e., carbon capture and storage or use). This approach is necessary because cement production generates unavoidable process emissions that cannot be eliminated completely, even in the long term.

The first and third approach have no direct influence on the manufacturing process of concrete products. However, the situation is different for the second approach since what all low-carbon types of cement have in common is their lower heat of hydration and thus the release of less heat during curing, which can slow down the process. This phenomenon will be explained using the example of calcined clay.

Calcined clays play a major part in decarbonizing the cement industry because they allow for the clinker ratio in the cement to be reduced significantly without compromising the strength or durability of the concrete. Calcined clays are activated by heating (calcination) at temperatures between approximately 600 °C and 850 °C. Activation means that crystal water and other chemical compounds are removed from the clay, which results in a highly reactive material that exhibits pozzolanic properties in cement production. Calcined clays thus offer two significant advantages over cement clinker: Firstly, they are activated at about 800 °C, which is a much lower temperature than 1,450 °C required for limestone deacidification, and thus consume significantly less energy. Secondly, calcination only produces metakaolin and water vapor, but no additional carbon dioxide.

Effects on the curing process

As positive as these properties may be in terms of avoiding carbon emissions, the question arises as to whether there are any consequences for the curing process of concrete products.

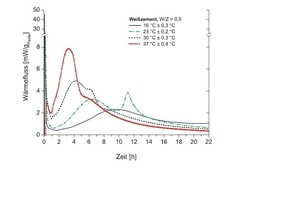

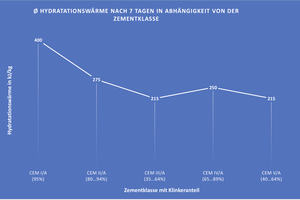

As explained above, low-carbon types of cement exhibit a lower reactivity than pure clinker, which slows down hydration during the curing process of concrete products. We should bear in mind, though, that heat release is also significantly reduced owing to the lower clinker ratio. While commercially available Portland cement of class CEM I exhibits a heat of hydration of 300-400 kJ/kg of cement, calcined clays only reach about 50% of this value, namely 150-250 kJ/kg. The above factors mean that early strength, which is exceedingly important for the manufacture of concrete products, is reached more slowly. Fig. 1 shows the extent of the loss of hydration heat when using sustainable cement compared to a conventional CEM I Portland cement.

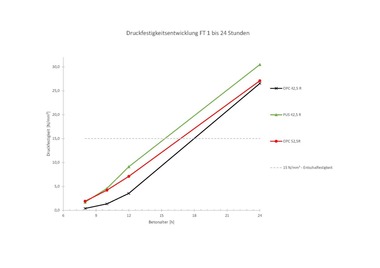

This development has significant implications for concrete curing. In state-of-the-art plants for concrete products, concepts such as time to market and in-line curing are important drivers that ensure the competitiveness of our industry. This is why the focus must be on the curing process to avoid production-related disadvantages when using low-carbon cement.

Slower reaction and lower heat of hydration

The slower reaction rate and lower heat of hydration resulting from the use of low-carbon cement require, as a minimum, optimal utilization of this heat through good insulation of the climate chamber and an efficient air circulation system that distributes the heat evenly. Whether this is then sufficient for the process depends on several factors, including the number of shifts worked in production and the cement content of the concrete. However, it will likely no longer be possible to not use active heating of the curing chamber. Active heating is also a good option for counteracting the current trend in cement development. According to the Arrhenius equation known from chemical kinetics, this is because the speed of any chemical reaction increases with temperature. This dependency is effectively demonstrated when measuring the build-up of hydration heat in white cement (see Fig. 2).

This figure shows that the higher the temperature during curing, the faster the heat of hydration of the cement will be released. Active heating can thus contribute to at least partially offsetting the lower heat of hydration from sustainable cement if high early strength is required. Active heating of the curing chamber thus makes it possible to use sustainable cement and to lower carbon emissions without having to tolerate major shortcomings during curing.

Consideration of thermal energy requirements

We could then argue that the reduction in carbon emissions thanks to the use of sustainable cement may be eaten up by the emissions from active heating of curing chambers. However, we should bear in mind that even low-carbon cement still has a high thermal energy requirement in production, even if reduced by a considerable 10-30% for class CEM II and even 20-40% for class CEM IV compared to a CEM I. The thermal energy requirement of active curing chamber heating is relatively low. By way of approximation, active heating consumes only about 3-5% of the thermal energy saving referred to above. These figures seem plausible when considering that, in this case, the curing temperature currently increases by only 30 to 35 °C, which is a completely different order of magnitude compared to the difference of several hundred degrees Celsius in cement production.

Active heating of curing chambers

Many concrete product manufacturers have already added active heating to their curing chambers, but not all producers are using it yet. This is most likely due to the associated investment and operating costs. Investing in active curing chamber heating is also likely to pay off in the future since carbon emissions are already factored into the price of cement and the cost of carbon emissions trading certificates is increasing steadily.

When evaluating the active heating option, it should also be noted that cement costs are likely to rise at the beginning of 2026. This is because imports of inexpensive cement will then be subject to the cost of carbon emission certificates (CBAM certificates) to avoid distortions of competition. Active heating can also help in this case because the accelerated development of hydration heat tends to lower cement consumption, which could offset higher cement costs at least to a certain extent. However, this scenario must be assessed separately for each individual use case.

Starting from the assumption that active heating can compensate for the disadvantages of low-carbon cement in the curing of concrete products, the next logical question is which heating option is best suited for this purpose. The following sections thus provide some basic information on the various sources of energy to make it easier to select the most appropriate heating solution:

Fossil fuels: Heating methods using fossil fuels are tried and tested, available worldwide, and relatively inexpensive. However, because of the socio-political debate and climate policy goals, it is highly likely that such processes will have to be replaced by carbon-neutral alternatives in the medium term.

Solar thermal/photovoltaics: Investing in a photovoltaic system with the aim of reducing electricity costs, which remain largely constant over the year, may seem reasonable in principle. However, the situation is different with thermal energy. In concrete curing, thermal energy is primarily required during the cooler half of the year, when little or no energy is available from solar thermal or photovoltaic systems. Without affordable storage options for heat and electricity, this option thus does not appear to make sense currently.

Electricity/heat pumps: Electricity combined with a heat pump is generally a viable alternative for climate-neutral generation of the required thermal energy. However, investment in an industrial heat pump is significantly higher compared to fossil heat generators and only pays back over a prolonged period. It is also necessary to check on-site whether a sufficient heat source, such as geothermal energy or waste heat, is available because the heat pump as such does not generate any energy. Rather, it takes thermal energy from a lower-temperature reservoir and transfers it as useful heat to a system to be heated up to a higher temperature. The quality of the energy source is thus crucial for the efficiency of the heat pump.

Overall, none of the options mentioned for active curing chamber heating can be recommended without reservation. This is why another option deserves closer consideration that adds flexibility to the process of selecting the heating system, which is hot water generation.

Even though water is not a source of energy, it can transport large quantities of heat and feed it into a process controlled through heat exchangers. If the curing chamber is equipped with appropriate heat exchangers and a hot water circuit, either a single or several different heat generation sources can be connected at one end. For example, an initially installed gas-fired condensing boiler can later be replaced by a heat pump without having to dismantle the entire heating system.

Heating solutions favored by Rotho

The above-mentioned heating solution favored by Rotho is currently becoming increasingly popular – for several reasons:

The decision in favor of a particular technical process can be adjusted quite easily at a later point in time.

Rotho provides its customers with the option of generating their own hot water. This allows customers to drive down their heating costs. Another advantage is that a local contractor can service the heating system.

Installing heat exchangers in the individual circuits of the Rotho ProAir air circulation system results in a very uniform climate in the entire curing chamber. In conjunction with a smart control system, installation of several heat exchangers allows heat to be fed into the curing chamber exactly where it is needed.

Optionally, waste heat from hydraulic cooling and air compressors can be fed into the hot water circuit.

Rotho air circulation systems can be retrofitted with hot water heating at any time.

Conclusion

Thanks to innovative developments in the cement industry, concrete producers currently have access to types of cement with a significantly lower carbon footprint. However, such sustainable types of cement are less reactive and generate a lower heat of hydration, which adversely affects the curing process of concrete products. Producers who want to prepare themselves for using climate-friendly cement in the future can partially offset these disadvantages through active heating. Regarding the most suitable heating option, heat transfer through heat exchangers and a hot water circuit has proven to be an efficient process in a real-life factory environment. This setup can be implemented using various sources of energy for hot water generation and combined with heat recovery.

CONTACT

Robert Thomas

Metall- und Elektrowerke GmbH & Co. KG

Hellerstr. 6

57290 Neunkirchen/Germany

+49 2735 788-0