Novel types of concrete and their potential applications

This article describes various novel types of concrete and discusses their potential range of applications and intended uses.

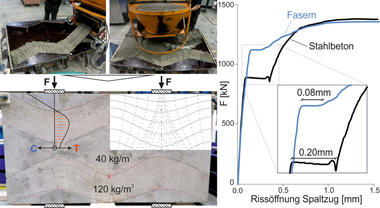

1 Fiber-reinforced concrete

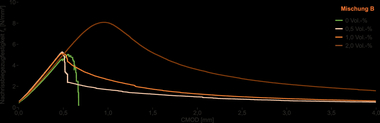

Fiber-reinforced concrete is a relatively new type of concrete compared to the “conventional” synthetic building material. Fibers are added to the concrete during production to enhance its hardening characteristics and thus material properties such as compressive strength, tensile strength, and cracking behavior. This means that, unlike conventional concrete, fiber-reinforced concrete can also absorb tensile forces even in the uncracked state. Cement fiberboards are also available at building materials merchants; they are suitable for use in damp rooms instead of gypsum fiberboards or other drywall boards.

In addition to sand or gravel, the Romans added plant fibers or animal hair to the fresh concrete. This prevented shrinkage cracks from forming, and the hardened concrete could also absorb tensile forces. This manufacturing method was adapted from brick production because the same effect of shrinkage cracking had to be prevented there. Until the early 20th century, natural fibers were used in concrete and mortar, as well as in plaster. It was only with the introduction of steel-reinforced concrete and its invention in 1867 by French gardener and building contractor, Monier, in which the steel absorbs the tensile load component, that the addition of fibers was abandoned. It is also worthy of note that adding natural fibers to fresh concrete is no longer permissible under currently applicable standards.

Starting in 1950, tests were conducted with steel fibers, which were mainly designed to prevent shrinkage cracking during the setting process of the fresh concrete. From 1970, this gave rise to steel fibers being added to fresh concrete as thin, often corrugated wires. Subsequently, glass or plastic fibers were also added to fresh concrete. At that time, no design methods for the structural verification of steel-fiber-reinforced concrete were available. This is why guidelines and standards approved fiber-reinforced concrete only as a “secondary” construction material. This meant that load-bearing components could not be made of fiber-reinforced concrete. Bernhard Wietek, Austrian civil engineer with a focus on geotechnical engineering, developed specific verification methods to analyze fiber-reinforced concrete using the required characteristic values such as compressive, tensile, and shear strength, but these methods have not yet been incorporated into current guidelines or standards.

In structural terms, fiber-reinforced concrete acts like a homogeneous construction material comparable to brick, steel, or standard concrete and, like all homogeneous materials, has good load-bearing characteristics in the uncracked state. Like conventional concrete, fiber-reinforced concrete is highly durable. Ancient concrete buildings such as the Pantheon in Rome are about 2,100 years old. In loaded condition, steel-reinforced concrete transfers compressive forces to concrete and tensile forces to steel. This leads to a cracked state that must be considered in the verification and construction of reinforced concrete structures. Although the steel is protected in the concrete by the alkalinity of the cement paste, this protective element is no longer fully present in the cracked state. External exposure to salt, such as on roads and bridges, poses a substantial risk of corrosion to the reinforcing steel. This leads to a service life of only 30 to 40 years for steel-reinforced concrete when used for transportation infrastructure.

Conversely, fiber-reinforced concrete is also associated with some shortcomings: During pouring, fibers can clog concrete pumps and hoses. Under unfavorable conditions, fibers can segregate prior to or during concrete placement. The material then no longer exhibits homogeneous properties. Moreover, the surface of concrete reinforced with fibers is more difficult to smooth. Finally, steel fibers can corrode and adversely affect the service life of structural components.

2 Polymer concrete

Polymer concrete differs from conventional concrete in that a plastic (polymer) rather than cement is used as a binder. It is thus not a cement , but a plastic matrix that locks the aggregates together in polymer concrete. This is a crucial factor because the polymer-based binder gives this type of concrete its specific properties.

In polymer concrete, the binder also needs to join mostly mineral aggregates, including gravel, sand, or stone dust, into a cohesive material. The plastic matrix consists of reactive resins. In the concrete production process, reactive resins are added to the aggregates in liquid form, after which they solidify. Reactive resins include, for example, unsaturated polyester resins, epoxy resins, or polyurethanes. Plastic, steel, or carbon fibers, or glass beads, can also be used as aggregates.

Like standard concrete, polymer concrete can be used in road construction for applications up to the highest BK 100 load class, which applies to highways and expressways. The fresh concrete mass in polymer concrete sets much faster than standard concrete. Polymer concrete is relatively lightweight, which makes it easier to transport and install. At the same time, the material is stronger than standard concrete. In addition, polymer concrete can withstand comparatively high tensile and bending stresses. Another advantage of polymer concrete is its exceptionally smooth, low-porosity surface, which is impervious to water. The material is exceedingly resistant to aggressive chemicals. Polymer concrete is thus often used for drainage channels, including in areas where substances hazardous to groundwater need to be handled. Furthermore, polymer concrete is dimensionally stable, even if exposed to major temperature fluctuations, as well as frost-proof, UV-resistant, corrosion-resistant, and non-combustible. In the construction industry, polymer concrete is also used for pipes, cable ducts, and light wells. Slabs, for example for steps or façade panels, balcony slabs, windowsills, tabletops, garden benches, or planters are also often made from polymer concrete. Due to its good vibration damping properties, this material is also used in the industrial construction sector, such as for constructing foundations or frames for equipment and machinery.

3 Carbon-reinforced concrete

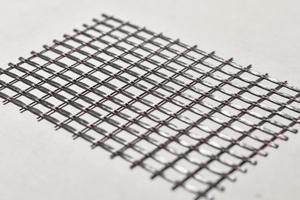

Carbon-reinforced concrete is a synthetic, nonmetallic, composite construction material similar to steel-reinforced concrete. It consists of two components, namely the concrete as such and a reinforcement made of carbon fiber mesh and bars. Owing to the manufacturing process, mesh-like reinforcement is often called a “textile”, and the concrete reinforced with it is generically referred to as textile-reinforced concrete.

The concept of carbon-reinforced concrete encompasses mesh-like and bar-shaped reinforcements made of carbon, but not alkali-resistant glass, basalt etc. In contrast, textile-reinforced concrete includes mesh-like reinforcements made of alkali-resistant glass and carbon or basalt, but no bar-shaped reinforcements made of these materials. This means that carbon-reinforced concrete is neither an umbrella term nor a subgroup of textile-reinforced concrete. Rather, the two designations overlap when it comes to the mesh-like reinforcement made of carbon.

In contrast to conventional reinforced concrete, whose reinforcement is made of steel, the reinforcement in carbon-reinforced concrete consists of continuous carbon fibers (filaments) processed into yarns or bars. The carbon-based reinforcing material used provides a tensile strength of about 3,000 N/mm², which exceeds the corresponding value of conventional reinforcing steel (approx. 550 N/mm²). Consequently, less reinforcing material is required. Prestressing steel has a tensile strength of 1,770 N/mm². Carbon-reinforced concrete is suitable for producing new and strengthening existing structural components. Fine-aggregate concretes with a maximum particle size under 2 mm and concretes with a maximum particle size smaller than or equal to 8 mm are used.

Carbon reinforcement is chemically inert to various actions relevant in the construction industry. It is not involved in certain chemical processes per se and, like reinforcing steel, need not be protected against corrosion by a concrete cover of several centimeters. It is thus possible to save material for components made of carbon-reinforced concrete, and significantly more slender component designs are possible.

Carbon reinforcement is produced as mesh and bars. Short carbon fibers are currently only of secondary significance and are not covered by the concept of carbon-reinforced concrete. Carbon bars are produced in a pultrusion (extrusion) process, usually in circular cross-sections and various diameters. Their surface is often profiled to ensure effective load transfer between the reinforcement and the concrete. The grid-like mesh reinforcement is produced using a textile processing method, which is why mesh reinforcement is often also referred to as a reinforcing textile. The concrete reinforced with it is also called textile-reinforced concrete. Mesh reinforcement is available in different yarn cross-sectional areas and mesh widths, including single layer 2D fabrics and 3D reinforcing structures.

Carbon fabrics are non-woven textile fabrics whose fibers lie endlessly and parallel next to each other and are held in place by a sewing thread or thermofixing. Carbon fabrics are used in fiber composites for maximum stability and bearing capacity. In contrast to woven fabrics, carbon fibers are oriented along one or more axes, including unidirectional, bidiagonal, bidirectional, triaxial, or quadraxial patterns. This design makes it possible to optimize load transfer and ensure high mechanical strength.

The Cube is the world’s first building constructed entirely from concrete with nonmetallic reinforcement. It is located on the TU Dresden campus and is the result of an interdisciplinary collaboration between industry and science under the umbrella of the C3 – Carbon Concrete Composite association. Cube consists of two doubly curved “twist shells,” which function as wall and roof, and a two-story box made of precast elements. This building demonstrates the fascinating interaction between dynamic design and cubist style influences. The Cube project successfully demonstrated the use of carbon-reinforced concrete in compliance with all relevant building regulations.

Its design is determined by the cast-in-place twist shells made of almost white carbon-reinforced concrete, which are up to 6.8 m high and 32.0 m long. These shells show an identical geometry and are twisted in relation to each other. In conjunction with a light strip, they form the roof surface and are also part of the outer shell of the Cube owing to their twisting from the horizontal to the vertical plane. The wings project about 8 m from the base of the building and are only 6 cm thick at their outer ends.

The twist shells surround the cuboid, two-story (semi-)prefabricated box made of dark-shaded carbon-reinforced concrete. The box is approximately 10.7 m long, 4.9 m wide, and 6.8 m high. It consists of twenty-five semi-precast walls, ten parapet elements, nine precast hollow-core slabs, and two flights of stairs. These components were joined together on-site using cast-in-place concrete to form the load-bearing structure.

4 Glass-fiber-reinforced plastic

Glass-fiber-reinforced plastic (GFRP or GRP) is a fiber-plastic composite composed of a plastic and glass fibers. Both thermosetting plastics, such as polyester resin or epoxy resin, and thermoplastics, such as polyamide, can be used as base materials.

Continuous glass fibers were first produced industrially in the United States in 1935 for reinforcing purposes. Mass production was developed in the 1930s by Games Slayter (Owens Corning) and other companies. At that time, the material was mainly used to insulate buildings. The material was subsequently used in cars in the 1950s, including in the Kaiser Darrin and the first Corvette. The first aircraft made of glass-fiber-reinforced plastic was the Fs 24 Phoenix designed by Akaflieg Stuttgart in 1957.

GRP is also colloquially referred to as fiberglass, which is the previously used word for glass fiber. In the non-specialist world, “fiber” is often only used when referring to GRP or carbon-fiber-reinforced plastic (CFRP). However, this term always refers to fiber-reinforced plastics since components could not be manufactured without the plastic matrix that lends shape and surface to them.

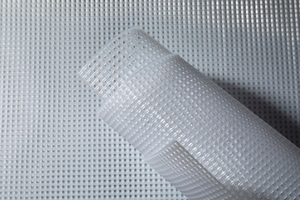

Glass-fiber-reinforced plastics are cost-effective yet high-quality fiber-plastic composites. In components subject to high mechanical loads, glass-fiber-reinforced plastic is used exclusively as continuous fiber in woven fabrics or unidirectional strands, i.e., strands of fiber-plastic composites oriented in just one direction. Compared to fiber-plastic composites made of other reinforcing fibers, glass-fiber-reinforced plastic combined with a suitable plastic matrix has a high elongation at break, high elastic energy absorption, but also a relatively low modulus of elasticity, which is lower than that of aluminum even in the fiber direction. Glass-fiber-reinforced plastic is thus unsuitable for components with high stiffness requirements, but it is suitable for leaf springs and similar parts.

Glass-fiber-reinforced plastic exhibits exceptionally good corrosion behavior even in aggressive environments. It is thus often used for containers and tanks in plant engineering, or for boat hulls. Since such hulls are non-magnetic, the material has been used for the construction of minesweepers since 1966. Glass-fiber-reinforced plastic with a suitable matrix provides good electrical insulation properties, which is why the material is also frequently used in electrical engineering. More specifically, insulators that need to transfer high mechanical loads are often made from glass-fiber-reinforced plastic. Control cabinets for outdoor use are frequently made of GRP due to the material’s durability and stability. Glass-fiber-reinforced plastic is also used for wind turbine rotor blades.